2024 – The Year of Democratic Reckoning

Do we want democracy, and if so, how can we save it in the age of AI?

Join the Impact Drive Community

Impact Drive is a platform that brings together young leaders interested in ethical entrepreneurship, social impact, and the future potential of artificial intelligence. If you want to join a community of highly motivated and talented present and future leaders, you can join this WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/BacTqFYxG1p68CzYlUhFew.

Apart from the high talent density of our community, what sets Impact Drive apart is our dedication to welcome open discussions, and our commitment to helping you form meaningful connections with other members.

Apply to write for Impact Drive

We also invite people to publish articles for Impact Drive. You can pitch your abstract (200 words) to impactdrive@substack.com. You can write about ethics, entrepreneurship, social impact, or artificial intelligence.

Our readers include students and graduates from leading universities (Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, and more), entrepreneurs of Unicorns, and employees at top companies.

Our first guest publisher is Varya Srivastava, who is currently researching the future of AI and Democracy for her Masters at the University of Oxford.

2024 – The Year of Democratic Reckoning

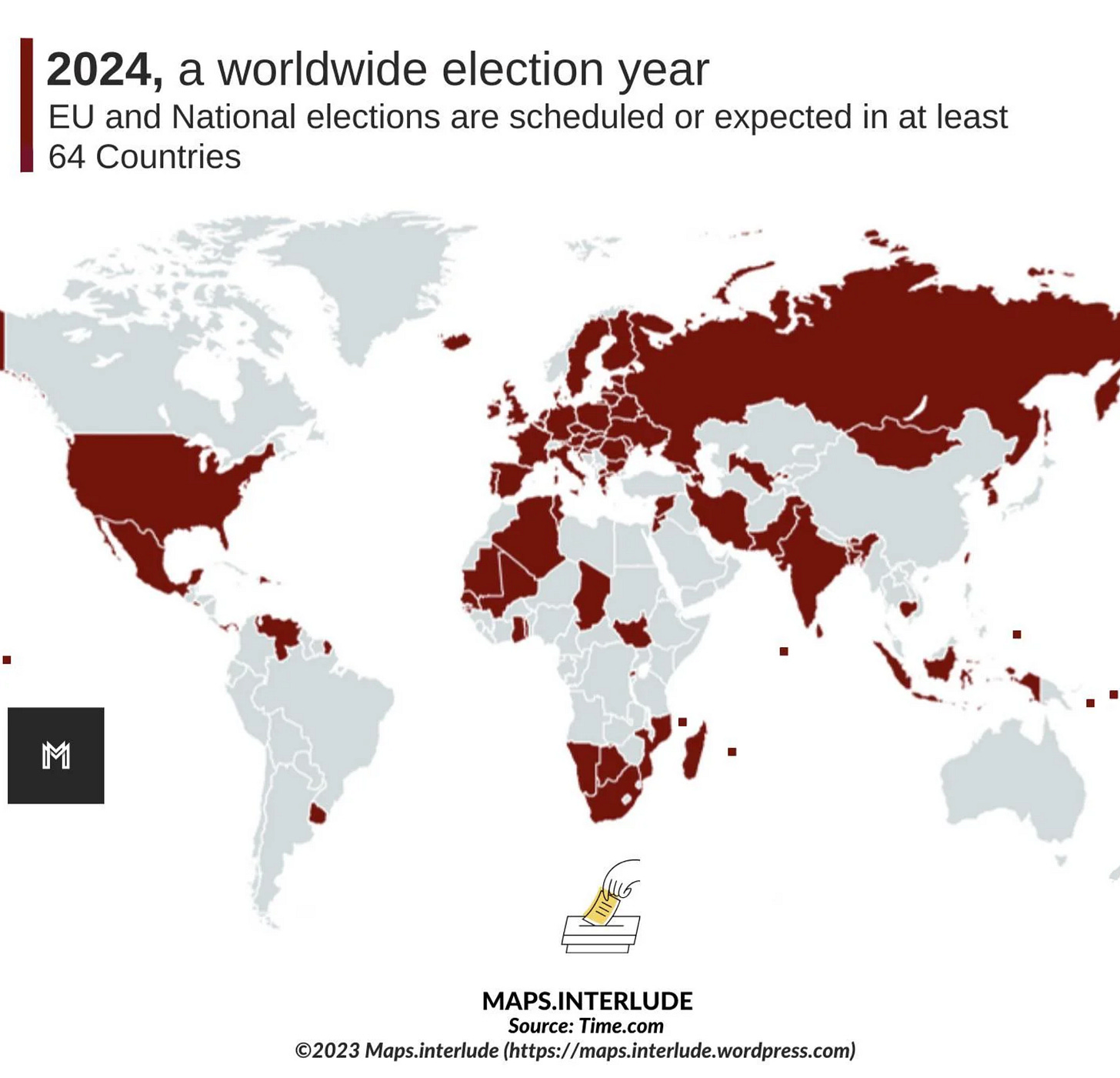

We are facing the “ultimate election year” with at least sixty countries set to hold their general or presidential elections between 2024-2025. This list includes the United States of America, India, Russia, Ukraine, United Kingdom and Australia, amongst others. These elections come at a time when, according to Freedom House, democratic governance continues to suffer a decline for the 19th consecutive year. It comes during a period of heightened political disillusionment and public apathy. Misinformation and deep-fakes could sway elections and create further mistrust amongst already deeply fragmented populations. The World Economic Forum notes how “deepfakes used by agenda-driven, real-time multi-model AI chatbots and avatars, will allow for highly personalised and effective types of manipulation.”

In response to this critical year of democratic decisions, global watchdogs are being activated and safeguards are being revised. Civil society is setting up independent platforms for media and information dissemination for different regions around the election. Tech platforms are updating their regulations on political communication. Local governments are adapting their election procedures in response to our increasingly digitalised public spheres.

In this newsletter, I want to take a step back and consider if democracy is even the way forward? And if yes, can we fix our democracies?

The Valley of Democracy

In a recent thought provoking personal essay, Oxford Researcher Ben Garfinkel asks a critical question – Is democracy a fad?

Garfinkel starts by observing how ‘democracy was rare for about five thousand years, and then became common over the course of about two hundred years’. He references the work of Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson to locate the rise of democracy two hundred years ago to be fueled by industrialisation. According to Acemoglu and Robinson, industrialisation helped align the political and economic preferences of the elites with that of the common public, thereby giving space to collective decision making. If we look beyond Garfinkel’s essay on democracy, we can also find justifications for the rise of democracy two hundred years ago in the European experience of the Enlightenment and the values of liberty, equality and fraternity it enshrined. Alternatively, in other parts of the world, democracy was brought about in resistance to colonialism.

Beyond the justification for the recent rise of democracy, the question Garfinkel attempts to engage with is whether democracy will survive this little valley between industrialisation and wide spread automation? A similar question is raised by Dr. Ted Lechterman, when he asks if AI will make democracy obsolete?

As we prepare for this 2024-25 election cycle that has more than half the earth’s population engaging in some form of collective decision making process, the questions by Garfinkel and Lechterman are more important than ever.

Do we want democracy?

An answer to the legitimacy of democracy often is found in the moral values it enshrines and its procedural effectiveness in creating relatively better laws and policies. Political philosophers have extensively engaged with this extensively and analysed all possible rationales to democracy. They have theorised its merits and limitations, and ultimately most conclude that it works because the people who are a part of the democracy want it to work. The legitimacy comes from the people.

Therefore, the questions Garfinkel and Lechterman raise are questions that citizens in democracies across the world must answer for themselves.

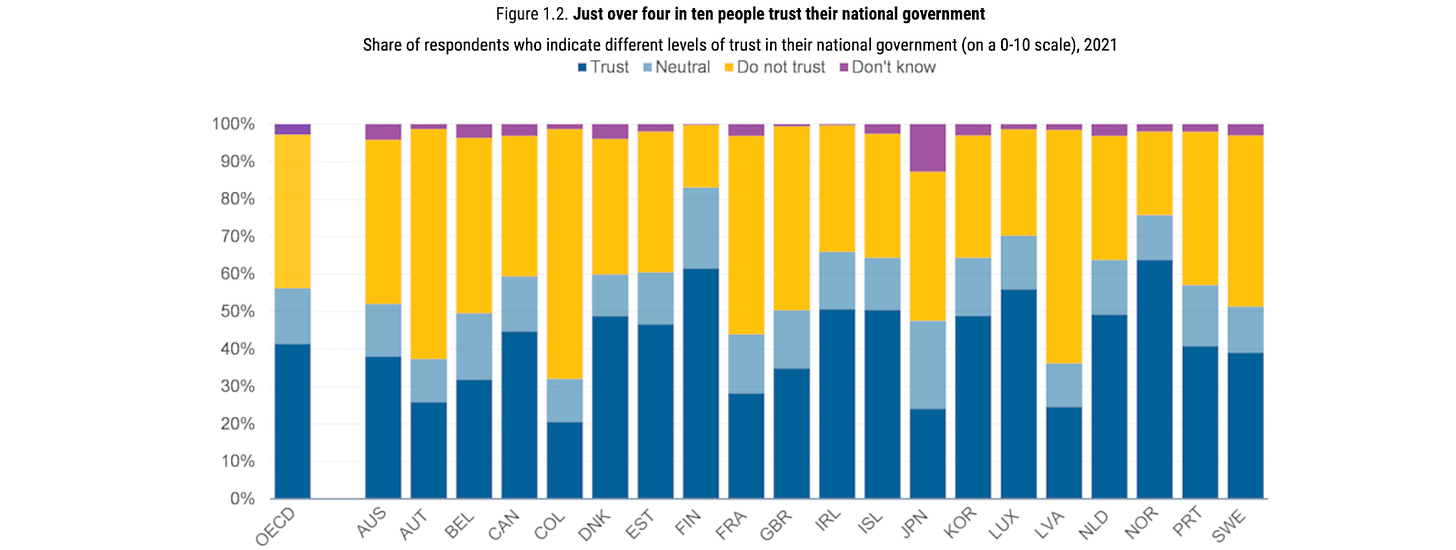

According to a 2021 OECD report ‘Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy’, it was found that just over four people (out of ten) trust their national governments. This decline in trust echoes the aforementioned Freedom House report that shows 2023 as the 19th consecutive decline in democratic governance. This makes the 2024 elections even more important.

In addition to exercising our right to the ballot, in 2024 we must decide if we want to continue the democratic tradition forward.

How do we fix democracy?

The good news is that there are academics and scholars working on answering these questions. We have Mark Coeckelbergh studying democracy and epistemic agency in our new AI and social media mediated digital public spheres. Hélène Landemore is engaging with new ways of thinking about the social epistemology of democracies by working on citizens’ assemblies. Sophia Rosenfeld is thinking about the place and nature of truth in our modern democracies. Zeynep Pamuk is working to identify the role of scientific knowledge and expertise in democratic decision making. Tarek Masoud explores the importance of religion and spirituality with the democratic tradition. Robert B Talisse reminds us that healthy democracies require fun and friendships to survive, while Elizabeth Cantalamessa asks us to embrace being sentimental for democratic success.

The not so good news is that it is still us who need to take all this theory and research on democracy and force it into practice.

The World Economic Forum outlines four measures we should take to guard against misinformation: Firstly, we can turn to technology itself: AI-based detection methods such as invisible watermarking can offer help in identifying deep fakes. These labelling techniques however face significant limitations and require appropriate detection tools. Secondly, policy measures such as the EU AI Act or the US Executive Order can mandate safety measures, promoting accountability and trust. Nonetheless, misuse risks remain as bad actors will invariably find ways around safeguards. Thirdly, we must invest in media literacy education: As individuals, we should be better equipped to identify deep fakes. In a study by Thinks Insight and Strategy, 4 in 10 users engaged with a deep fake of Keir Starmer (Leader of the UK Labour Party). However, those receiving misinformation “training” through a 45 second game were 42% less likely to engage with the fake message. This links with their final recommendation: We should adopt a “zero-trust mindset” where we don’t trust anything by default. In practice, of course, we cannot distrust and verify everything we see online. However, if we catch ourselves particularly surprised by a piece of information/ have the feeling that this piece of information has the chance to influence our views, we should try and verify it. Whilst the responsibility should ultimately not be wholly shifted to us as individuals, I think greater collective alertness can go a long way in protecting our democracy.

As the 2024-25 election cycle begins, we will invariably see moments of political chaos, public dismay and flawed electoral outcomes. We will see a polarised public sphere armed with misinformation that is mediated through private economic interest. We will continue to see power getting concentrated into the hands of unregulated technological players. In the face of all of this, we will have to work on translating emerging theories on democracy into practice. Until we as citizens demand it and use our democratic rights, we will not be able to fix the ruptures in our democracy.

Democracy, through all its conceptions and forms, has always been an experiment. It is never in a static state of application. It Through its meandering history it has always evolved in response to socio-economic-technological changes in the political units that it has been used in. This moment in democratic history is another point of inflection in the larger tradition of democracy.

The 2024-25 year of elections serves as the material and procedural reminder for us to rethink our democracies. In this year of democratic reckoning, while some countries might lose their battles of effective collective decision making, if we play our cards right we might still win the war against populism and totalitarianism. We might just be able to save democracy.

Thank you for reading and all the best,